The debate was only a few minutes old, and Barack Obama was already tanking. His opponent on this warm autumn night, a Massachusetts patrician with an impressive résumé, a chiseled jaw, and a staunch helmet of burnished hair, was an inferior political specimen by any conceivable measure. But with surprising fluency, verve, and even humor, Obama’s rival was putting points on the board. The president was not. Passive and passionless, he seemed barely present.

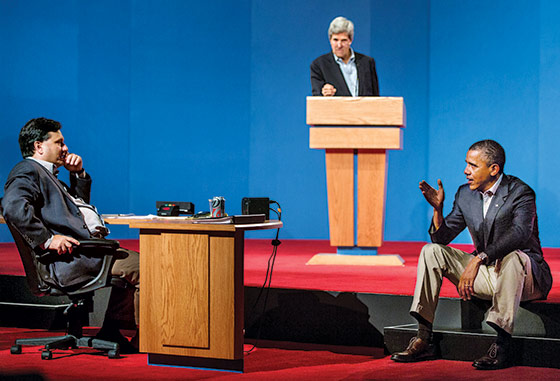

It was Sunday, October 14, 2012, and Obama was bunkered two levels below the lobby of the Kingsmill Resort in Williamsburg, Virginia. In a blue blazer, khaki pants, and an open-necked shirt, he was squaring off in a mock debate against Massachusetts senator John Kerry, who was standing in for the Republican nominee, Mitt Romney. The two men were in Williamsburg, along with the president’s team, to prepare Obama for his second televised confrontation with Romney, 48 hours away, at Hofstra University in New York. It was an event to which few had given much thought. Until the debacle in Denver, that is.

The debate in the Mile High City eleven days earlier had jolted a race that for many months had been hard fought but remarkably stable. From the moment in May that Romney emerged victorious from the most volatile and unpredictable Republican-nomination contest in many moons, Obama had held a narrow yet consistent lead. But after Romney mauled the president in Denver, the wind and weather of the campaign shifted in something like a heartbeat. The challenger was surging. The polls were tightening. Republicans were pulsating with renewed hope. Democrats were rending their garments and collapsing on their fainting couches.

Obama was nowhere in the vicinity of panic. “You ever known me to lose two in a row?” he said to friends to calm their nerves.

The president’s advisers were barely more rattled. Yes, Denver had been atrocious. Yes, it had been unnerving. But Obama was still ahead of Romney, the sky hadn’t fallen, and they would fix what went wrong in time for the town-hall debate at Hofstra. Their message to the nervous Nellies in their party was: Keep calm and carry on.

Williamsburg was where the repair job was supposed to take place. The Obamans had arrived at the resort, ready to work, on Saturday the 13th. The first day had gone well. The president seemed to be finding his form. He and Kerry had been doing mock debates since August, and the session on Saturday night was Obama’s best yet. Everyone exhaled.

But now, in Sunday night’s run-through, the president seemed to be relapsing: The disengaged and pedantic Obama of Denver was back. In the staff room, his two closest advisers, David Axelrod and David Plouffe, watched on video monitors with a mounting sense of unease—when, all of a sudden, a practice round that had started out looking merely desultory turned into the Mock From Hell.

The moment it happened could be pinpointed with precision: at the 39:35 mark on the clock. A question about home foreclosures had been put to potus; under the rules, he had two minutes to respond. Before the mock, Kerry had been instructed by one of the debate coaches to interrupt Obama at some juncture to see how he reacted. Striding across the bright-red carpet of the set that the president’s team had constructed as a precise replica of the Hofstra town-hall stage, Kerry invaded the president’s space and barged in during Obama’s answer.

The president’s eyes flashed with annoyance.

“Don’t interrupt me,” he snapped.

When Kerry persisted, Obama shot a death stare at the moderator—his adviser Anita Dunn, standing in for CNN’s Candy Crowley—and pleaded for an intercession.

The president’s coaches had long worried about the appearance of Nasty Obama on the debate stage: the variant who infamously, imperiously dismissed his main Democratic rival in 2008 with the withering phrase “You’re likable enough, Hillary.” His advisers saw glimpses of that side of him in their preparations for the first showdown—a manifestation of a personal antipathy for Romney that had grown visceral and intense. Now they were seeing it again, and worse. The admixture of Nasty Obama and Denver Obama was not a pretty picture.

Challenged by Kerry with multipronged attacks, the president rebutted them point by point, exhaustively and exhaustingly. Instead of driving a sharp message, he was explanatory and meandering. Instead of casting an eye to the future, he litigated the past. Instead of warmly establishing connections with the town-hall questioners, he pontificated airily, as if he were conducting a particularly tedious press conference. While Kerry was answering a query about immigration, Obama retaliated for the earlier interruption by abruptly cutting him off.

Excerpted from Double Down: Game Change 2012, by Mark Halperin and John Heilemann, to be published on November 5, 2013, by the Penguin Press.

In the staff room, Axelrod and Plouffe were aghast. Sitting with them, Obama’s lead pollster, Joel Benenson, muttered, “This is unbelievable.”

Watching from the set, the renowned Democratic style coach Michael Sheehan scribbled furiously on a legal pad, each notation more alarmed than the last. Reflecting on Obama’s interplay with the questioners, Sheehan summed up his demeanor with a single word: “Creepy.”

After 90 excruciating minutes, the Mock From Hell was over. As Obama made his way to the door, he was intercepted by Axelrod, Plouffe, Benenson, and the lead debate coach, Ron Klain. Little was said. Little needed to be said. The ashen looks on the faces of the president’s men told the tale.

Obama left the building and returned to his sprawling quarters on the banks of the James River with his best friend from Chicago, Marty Nesbitt, to watch football and play cards. His advisers retreated to the president’s debate-prep holding room to have a collective coronary.

That the presidential debates were proving problematic for Obama came as no real surprise to the members of his team. Many of them—Axelrod, the mustachioed message maven and guardian of the Obama brand; Plouffe, the spindly senior White House adviser and enforcer of strategic rigor; Dunn, the media-savvy mother superior and former White House communications director; Benenson, the bearded and noodgy former Mario Cuomo hand; Jon Favreau, the dashing young speechwriter—had been with Obama from the start of his meteoric ascent. They knew that he detested televised debates. That he disdained political theater in every guise. That, on some level, he distrusted political performance itself, with its attendant emotional manipulations.

The paradox, of course, was that Obama had risen to prominence and power to a large extent on the basis of his preternatural performance skills—and his ability to summon them whenever the game was on the line. In late 2007, when he was trailing Hillary Clinton in the Democratic-nomination fight by 30 points. In the fall of 2008, when the global financial crisis hit during the crucial last weeks of the general election. In early 2010, when his signature health-care-reform proposal seemed destined for defeat. In every instance, under ungodly pressure, Obama had pulled up, set his feet, and drained a three-pointer at the buzzer.

The faith of the president’s people that he would do the same at Hofstra was what sustained them in the wake of Denver. For a year, the Obamans had fretted over everything under the sun: gas prices, unemployment, the European financial crisis, Iran, the Koch brothers, the lack of enthusiasm from the Democratic base, Hispanic turnout in the Orlando metroplex. The one thing they had never worried about was Barack Obama.

But given the spectacle they had just witnessed at Kingsmill, the Obamans were more than worried. After spending ten days pooh-poohing the widespread hysteria in their party about Denver, Obama’s debate team was now the most wigged-out collection of Democrats in the country, huddling in a hotel cubby that had become their secret panic room. Three hours had passed since the mock ended; it was almost 2 a.m. Obama’s team was still clustered in the work space, reading transcripts and waxing apocalyptic.

“Guys, what are we going to do?” Plouffe asked quietly, over and over. “That was a disaster.”

Among the Obamans, there was nobody more unflappable than Plouffe—and nobody less shaken by Denver. But while Plouffe believed the public would brush off a single bad debate showing, he was equally convinced that two in a row would not be so readily ignored. If Obama turned in a performance at Hofstra like the one they had seen that night, the consequences could be dire.

“If we don’t fix this,” Plouffe said emphatically, “we could lose the whole fucking election.”

Almost from the moment that Obama stepped off the debate stage in Denver, he had been bombarded with advice about how to remedy what had gone wrong. But the truth was that virtually no one on the planet could understand what he was going through or up against.

A rare exception was Bill Clinton. Before Denver, Clinton had watched in wonder as Obama caught break after break. Although the economy wasn’t roaring back, neither the European banking crisis nor the unrest in the Mideast had caused it to nosedive. Meanwhile, Romney’s ineptness staggered Clinton. After the release of the 47 percent video, he remarked to a friend that, while Mitt was a decent man, he was in the wrong line of work. (“He really shouldn’t be speaking to people in public.”) As for Obama, Clinton trotted out for his pals the same line again and again: “He’s luckier than a dog with two dicks.”

Though the first debate brought the incumbent’s streak of good fortune to a crashing halt, Clinton was insistent that the Obamans not overreact. On the phone to Axelrod, 42 counseled restraint at Hofstra, warning that if 44 was too hot or negative in a town-hall debate, it would backfire. Four days after Denver, at a fund-raiser at the Beverly Hills home of Hollywood mogul Jeffrey Katzenberg, Clinton huddled with Obama and repeated the instructions.

Don’t try to make up the ground you lost, the Big Dog said. Just be yourself.

Obama faced a more immediate challenge, which was to arrest the metastasizing panic among his supporters. In 2008, Plouffe had airily dismissed Democrats who lost their minds in the midst of Palinmania as “bedwetters.” But now there was a similar drizzle as the public polls sharply narrowed—and worse. “Did Barack Obama just throw the entire election away?” blared the title of an Andrew Sullivan blog post.

Chicago’s internal polling strongly suggested that the answer was no—the race was back to where it had been following the party conventions, with Obama holding a three- or four-point lead.

Even so, as the full desultoriness of his Denver performance sank in, the president was consumed by a sense of responsibility—and shadowed by fears that his reelection was at risk. Outwardly, he took pains to project the opposite. When his staffers asked how he was doing, he replied, “I’m great.” To Plouffe, who had volunteered to soothe Sullivan, Obama joked, Someone’s gotta talk him off the ledge!

Obama returned from the West Coast and met with his debate team in the Roosevelt Room on the afternoon of October 10. He opened by saying he had read a memo drafted by Klain about what went awry in Denver and how to fix it before Hofstra, now six days away. He agreed with most of it but wanted everyone to know that they hadn’t failed him; he had failed them. “This is on me,” Obama said.

“I’m a naturally polite person,” he went on. Part of my problem is “erring on the side of being muted. We have to get me to a place where internally I’m not biting my tongue … It’s important for me to be fighting.”

The debate team received a boost 24 hours later from Obama’s second-in-command, when Joe Biden took on Paul Ryan in the vice-presidential debate in Danville, Kentucky. “You did a great job,” the president told the V.P. by phone. “And you picked me up.”

In 36 hours, Obama would set off for debate camp in Williamsburg. But watching his understudy had already provided him with one helpful insight.

“These are not debates,” Obama observed to Plouffe. “These are gladiatorial enterprises.”

The first lady worried about her Maximus and his return to the Colosseum. In truth, she had fretted over the debates even before Denver. In July, around the time her husband’s prep started, she met with Plouffe and expressed firm opinions. That Barack had to speak from the gut, in language that regular folks could understand. Had to avoid treating the debates like policy seminars. Had to keep his head out of the clouds. (Michelle’s advisers paraphrased her advice as “It’s not about David Brooks; it’s about my mother.”) FLOTUS loved POTUS like nobody’s business, but she knew his faults well.

In the wake of Denver, Michelle was unfailingly encouraging with her husband: Don’t worry, you’re going to win the next one, just remember who you’re talking to, she told him. Before a small group of female bundlers, she pronounced that Barack had lost only because “Romney is a really good liar.”

Privately, however, Michelle was unhappy about how her spouse’s prep had been handled. There had been a late arrival in Denver, a rushed dinner at a crappy hotel. Inexplicably, he had been unable to reach Sasha and Malia by phone. He seemed overscheduled, overcoached, and under-rested. At first, Michelle conveyed her displeasure via senior White House adviser and First Friend Valerie Jarrett, who flooded the in-boxes of the debate team with pointed e-mails, employing the royal “we.” But the day before debate camp in Williamsburg, Michelle delivered marching orders directly to Plouffe: If the president wants our chef there, he should be there; if he wants Marty Nesbitt there, he should be there. Barack’s food, downtime, exercise, sleep, lodging—all of it affects his frame of mind. All of it has to be right.

Plouffe saluted sharply and thought, I guess the First Lady understands the stakes here.

That same Friday, October 12, Obama’s debate team gathered again in the Roosevelt Room for a final pre-camp session. The president was presented with a piece of overarching advice and a memo, both of which would have been inconceivable before Denver. The advice was: Be more like Biden, whose combativeness, scripted moments, and bluff calls on Ryan (“Not true!”) the night before had all proved effective tactics. The memo was an alliterative flash card to remind Obama of what it called “the Six A’s”:

Advocate (don’t explain)

Audience

Animated

Attacks

Answers with principles and values

Allow yourself to take advantage of openings

Ron Klain had no shame about such contrivances—whatever worked. A Washington super-staffer, Klain had served on every Democratic presidential debate-prep team for twenty years and co-led Obama’s effort in 2008. But his relationship with the president was not straightforward or particularly close. Right after the Denver disaster, he offered to resign from the debate team, but Obama refused to let him. Klain’s ego, pride, and future ambitions were all wrapped up in correcting the miscues from the Mile High City and constructing a comeback at Hofstra.

Klain turned Obama’s prep regime upside down: new strategy, new tactics, new structure. In Williamsburg, there would be an intense concentration on performance, including speeding up Obama’s ponderous delivery. There would be less policy Q&A and more rehearsal of set pieces and lines that popped. Less emphasis on programmatic peas and spinach, more on anecdote and empathy. Contrary to Clinton’s advice, there would be plenty of punching to go along with the counterpunching.

Camp commenced on Saturday in Williamsburg. Two levels down from the lobby of the Kingsmill Resort Center, on the precisely built replica of the Hofstra town-hall set, the president spent most of the day sharpening his answers with Klain and Axelrod. That night, his mock went better than any of the six sessions prior to Denver. The members of the debate team weren’t ready to declare victory yet, but they were relieved. Obama’s friend Nesbitt was exultant.

“That’s some good shit!” he told the president, patting him on the back. “That’s my man! He’s back!”

In the Sunday daytime sessions, Obama showed still more improvement, honing a solid attack on the 47 percent and another on his rival’s economic agenda. (“Governor Romney doesn’t have a five-point plan; he has a one-point plan, and that’s to make sure folks at the top play by a different set of rules.”) As the team took time off for dinner before Obama and Kerry went at it again, Klain thought, Okay, we’re getting to a better place. Plouffe thought, He’s locked in.

A little before 9 p.m., they returned to the Resort Center. Obama and Kerry grabbed their handheld microphones and took their places—and the president proceeded to deliver the Mock From Hell.

Even before Nasty Obama snarled at Kerry-as-Mitt and Anita Dunn as CNN’s Candy Crowley at the 39:35 mark, Klain was mortified. The president’s emotional flatness from Denver was back. He was making no connection with the voter stand-ins asking questions. He was wandering aimlessly, digressing compulsively, not merely chasing rabbits but stalking them to the ends of the Earth. His cadences were hesitant and maple-syrupy slow: phrase, pause, phrase, pause, phrase. His answers were verbose and utterly devoid of message.

In Klain’s career as a debate maestro, he had been involved in successes (Kerry over Bush three times in a row) and failures (Gore’s symphony of sighs in 2000). But he had never seen anything like this. After all the happy talk from Obama and his consistent, if small, steps forward, the president was regressing—with 48 hours and only one full day of prep between them and Hofstra.

At the Pettus House, a colonnaded red- brick mansion on the riverbank where Obama and Nesbitt were bunking, the two men stayed up late hashing out what hadn’t worked, how the president was still struggling to find the zone. “You can’t get mad” at Romney’s distortions, Nesbitt said. “You come off better when you just say, ‘Now, that’s fucking ridiculous.’ When you laugh, that shit works, man.”

In Obama’s hold room at the Resort Center, his staff was moving past puzzlement and panic toward practical considerations. The lesson that Plouffe had taken from Denver was that you could no longer count on fourth-quarter Obama; what you saw in practice was what you got on the debate stage. If he doesn’t have a good mock tomorrow, there’s no reason to believe that it’ll get fixed when he gets to New York, Plouffe said.

Two schools of thought quickly emerged within the team. The first, pushed by Washington super-lawyer Bob Barnett—who was also a longtime debate prepper and was there serving on Kerry’s staff—was that Obama needed to be shown video in the morning. “This is what we did with Clinton,” Barnett sagely noted. The other, advanced by Favreau, was that Obama should be given transcripts. He’s a writer, Favreau argued. Words on the page will make a deeper impression.

The full transcript was in hand within 45 minutes—and became a source of gallows humor. As the clock ticked well past midnight, Favreau stagily read aloud some of Obama’s most dreadful answers. Soon his colleagues joined in, with Axelrod, Benenson, and Plouffe offering recitations and laughing deliriously over the absurdity and horror of the circumstances.

Barnett and others believed that Obama’s playbook had to be stripped down more dramatically, to a series of simple and crisp bullet points on the most likely topics to come up in the debate. Klain agreed and wanted to go a step further. In 1996, Democratic strategist Mark Penn had devised something called “debate-on-a-page” for Gore in his V.P. face-off with Jack Kemp. Klain suggested they do the same for Obama: a sheet of paper with a handful of key principles, attacks, and counterattacks.

Axelrod and Plouffe thought something more radical was in order. For the past six years, they had watched Obama struggle with his disdain for the theatricality of politics—not just debates, but even the soaring speeches for which he was renowned. Obama’s distrust of emotional string-pulling and resistance to the practical necessities of the sound-bite culture: These were elements of his personality that they accepted, respected, and admired. But they had long harbored foreboding that those proclivities might also be a train wreck in the making. Time and again, Obama had averted the oncoming locomotive. Had embraced showmanship when it was necessary. Had picked his people up and carried them on his back to the promised land. But now, with a crucial debate less than two days away—one that could either put the election in the bag or turn it into a toss-up—Obama was faltering in a way his closest advisers had never witnessed. They needed to figure out what had gone haywire from the inside out. They needed, as someone in the staff room put it, to stage an “intervention.”

The next morning, October 15, Klain stumbled from his room to the Resort Center, eyes puffy and nerves jangled. He’d been up all night hammering together and e-mailing around his debate-on-a-page draft. In Obama’s hold room, the team members gathered and laid out their plan for the day. They would screen video for the boss. They would show him transcripts. They would present him with his cheat sheets. They would devote the day to topic-by-topic drills until he had his answers memorized.

Normally, the whole group would now meet with the president to critique the previous night’s mock. Instead, everyone except Axelrod, Klain, and Plouffe cleared the room just before 10 a.m. Obama was on his way. The intervention was at hand.

Where’s everybody else?” Obama asked as he ambled in across the speckled green carpet with his chief of staff, Jack Lew, at his side. “Where’s the rest of the team?”

We met this morning and decided we should have this smaller meeting first, one of the interventionists said.

Obama, in khakis and rolled-up shirtsleeves, looked nonplussed. Between his conversation with Nesbitt the night before and a morning national-security briefing with Lew, he was aware that his people were unhappy with the mock—but not fully clued in to the depth of their concern.

The president settled into a cushy black sofa at one end of the room. On settees to his left were Axelrod, Plouffe, and Lew; to his right, in a blue blazer, was Klain, now caffeinated and coherent.

“We’re here, Mr. President,” Klain began, “because we need to have a serious conversation about why this isn’t working and the fundamental transformation we need to achieve today to avoid a very bad result tomorrow night.” We’re not going to get there by continuing to grind away and marginally improve, Klain went on. This is not about changing the words in your debate book, because the difference between the answers that work and the answers that don’t work is just 15 or 20 percent. This is about style, engagement, speed, presentation, attitude. Candidly, we need to figure out why you’re not rising to and meeting the challenge—why you’re not really doing this, why you’re doing … something else.

Obama didn’t flinch. “Guys, I’m struggling,” he said somberly. “Last night wasn’t good, and I know that. Here’s why I think I’m having trouble. I’m having a hard time squaring up what I know I need to do, what you guys are telling me I need to do, with where my mind takes me, which is: I’m a lawyer, and I want to argue things out. I want to peel back layers.”

The ensuing presidential soliloquy went on for ten minutes—an eternity in Obama time. His tone was even and unemotional, but searching, introspective, diagnostic, vulnerable. Psychologically, emotionally, and intellectually, he was placing his cards face up on the table.

“When I get a question,” he said, “I go right to the logical.” You ask me a question about health care. There’s a problem, and there’s a response. Here’s what my opponent might say about it, so I’m going to counteract that. Okay, we’re gonna talk about immigration. Here’s what I’d like to say—but I can’t say that. Think about what that means. I know what I want to say, I know where my mind takes me, but I have to tell myself, No, no, don’t do that—do this other thing. It’s against my instincts just to perform. It’s easy for me to slip back into what I know, which is basically to dissect arguments. I think when I talk. It can be halting. I start slow. It’s hard for me to just go into my answer. I’m having to teach my brain to function differently. I’m left-handed; this is like you’re asking me to start writing right-handed.

Throughout the campaign, Obama had been criticized for the thin gruel of his second-term agenda. Now he acknowledged that it bothered him, too, and posed a challenge for the debates.

You keep telling me I can’t spend too much time defending my record, and that I should talk about my plans, he said. But my plans aren’t anything like the plans I ran on in 2008. I had a universal-health-care plan then. Now I’ve got … what? A manufacturing plan? What am I gonna do on education? What am I gonna do on energy? There’s not much there.

“I can’t tell you that ‘Okay, I woke up today, I knew I needed to do better, and I’ll do better,’ ” Obama said. “I am wired in a different way than this event requires.”

Obama paused.

“I just don’t know if I can do this,” he said.

Obama’s advisers sat silently at first, absorbing the extraordinary moment playing out in front of them. In October of an election year, on the eve of a pivotal debate, the president wasn’t talking about tactics or strategy, about this line or that zinger. He was talking about personal contradictions and ambivalences, about his discomfort with the campaign he was running, about his unease with the requirements of politics writ large, about matters that were fundamental, even existential. We are in uncharted territory here, thought Klain.

More striking was Obama’s candor and self-awareness. The most self-contained president in modern history (and, possibly, the most self-possessed human on the planet) was laying himself bare, deconstructing himself before their eyes—and admitting he was at a loss.

All through his career, Obama had played by his own rules. He had won the presidency as an outsider, without the succor of the Democratic Establishment. He owed it little, offered less. He had ignored the traditional social niceties of the office, and largely resisted the media freak show, swatting away its asininities. He had refused to stomp his feet or shed crocodile tears over the BP spill, because neither would plug the pipe spewing oil from the ocean floor. He had eschewed sloganeering to sell his health-care plan, although it meant the world to him.

Now he was faced with an event that demanded an astronomical degree of fakery, histrionics, and stagecraft—and while he was ready to capitulate, trying to capitulate, he found himself incapable of performing not just to his own exalted standards but to the bare minimum of competence. Acres of evidence and the illusions of his fans to the contrary, Barack Obama, it turned out, was all too human.

Axelrod was more intimate with Obama than anyone in the room. The president’s humanity and frailties were no secret to Axe—nor was 44’s capacity for self-doubt. Since Denver, Obama had been subjected to a hailstorm of criticism, a flood of panic, and a blizzard of psychoanalysis. Like every president, he claimed he was impervious to it. But Axelrod knew it was a lie. All this shit is in his head, the strategist thought.

Look, said Axelrod softly, we know that you find these debates frustrating, that they’re more performance than substance. It’s why you are a good president. It’s why all of us feel so strongly about your winning. But you have to find a way to get over the hump and stop fighting this game—to play this game, wrap your arms around this game.

For the next hour, the three Obamans tried to carry the president across the psychic chasm. Plouffe reminded him of the stakes. “We can’t have a repeat of Denver tomorrow night,” he warned. “Right now, we’re not losing any of our vote, but we’re on probation. If we have another performance that causes people to scratch their heads, we’re gonna start losing votes. We gotta stop this now.”

Over Obama’s despair about his lack of an agenda, Plouffe and Axelrod took him on. “You do have an agenda, goddammit!” Plouffe said. “This isn’t a bunch of b.s. you’re selling. This is an agenda the American people support and believe in. But they’re not gonna believe in it if you don’t treat it that way, by selling it with great fervor. If you sell your agenda and Romney sells his agenda with equal enthusiasm, we will win.

“Think about this,” Plouffe went on. “You have two debates left. So take out Romney, take out moderator questions: You’ve got basically 75 to 80 minutes left of doing this in your entire life. That’s less than the length of a movie! You can do this! I know it’s uncomfortable. I know it’s unnatural. But that’s all. That’s the finish line, you know?”

Klain employed a sports analogy. The Tennessee Titans lost the Super Bowl a couple of years ago because their guy got tackled on the one-yard line, he said—the one-yard line! That’s where we are. The hardest thing for any candidate in a debate is to know the substance. You have that down cold. All we need is a little more effort on performance. You need to go in there and talk as fast as you can. You need to add a little schmaltz, talk about stuff the way that people want to hear it. This isn’t about starting over, starting from scratch. We’ve got most of it right. The part we have left to get right is small. But as the Titans proved, small can mean the difference between winning and losing.

Obama’s aides couldn’t tell if their words were sinking in. “I understand where we are,” the president said finally. I’m either going to center myself and get this or I’m not. The debate’s tomorrow. There’s not much we can do. I just gotta fight my way through it.

As the meeting wound to a close, the Obamans felt relief mixed with trepidation. Oddly, for Klain, the president’s lack of confidence about his ability to turn himself around was comforting. After all the blithe I-got-its of his pre-Denver prep, Obama for the first time was acknowledging that a genuine and serious modification of his mind-set was necessary.

Plouffe felt less reassured. “It’s good news–bad news,” he told Favreau afterward. “The good news is, he recognizes the issue. The bad news is, I don’t know if we can fix it in time.”

The full team reconvened in Obama’s hold room. Klain ran through his memo of the previous night and explained to the president the new new format for his prep: For the rest of the day until his final mock, they were going to drill him incessantly on the ten or so topics they expected to come up in the debate, compelling him to repeat his bullet points over and over again. Klain also presented Obama with his debate-on-a-page:

MUST REMEMBER

1. (Your) Speed Kills (Romney)

2. Upbeat and Positive in Tone

3. Passion for People and Plans

4. OTR [Off the Record] Mind-set—Have Fun

5. Strong Sentences to Start and End

6. Engage the Audience

7. Don’t Chase Rabbits

BEST HITS

1. 47%

2. Romney + China Outsourcing

3. Heaven & Earth

4. 9/11 Girl

5. Sketchy Deal

6. Mass Taxes—Cradle to Grave

7. Preexisting and ER

8. Women’s Health

9. Borrow From Your Parents

REBUTTAL CHEAT SHEET

1. Jobs—The 1-point plan

2. Deficits—$7 trillion and The Sketchy Deal

3. Energy—Coal plant is a killer

4. Health—Preexisting fact check and the ER

5. Medicare—He wants to save Medicare … by ending it!

6. Bus Taxes—60 Mins in rebuttal (i.e., pivot to personal taxes)

7. Pers Taxes—Tax cuts for outsourcing (i.e., pivot to job creation)

8. Gridlock—Romney brings the lobbyist back

9. Benghazi—Taking offense

10. Education—Borrow from your parents and/or Size Doesn’t Matter

That the intervention had had some effect on Obama was immediately apparent, though how much was unclear. He brought a new energy and focus to his afternoon drills. When he delivered an imperfect answer, he stopped himself short: “Let’s do that again.” At his debate camp before Denver, outside Las Vegas, Obama had been so intent on escaping that he took off one day for a visit to the Hoover Dam. Now he refused even brief breaks for a walk by the river. As the afternoon went on, the debate team concocted cutesy catchphrases to cue him at the slightest hint of backsliding.

“Fast and hammy! Fast and hammy!” Klain would say when his delivery was lugubrious.

“Punch him in the face!” Karen Dunn, another team member, chipped in when he missed a chance to cream Kerry-as-Mitt.

For Klain, the turning point came that afternoon, during a session in which Obama was fielding questions from junior members of the team who were standing in as voters. Tony Carrk, a researcher, introduced himself as Vito, a barbershop proprietor from Long Island, and asked which tax plan—Obama’s or Romney’s—would be better for small-business owners like him. Without missing a beat, the president savaged Mitt’s plan with verve, precision, and bite, closing with some good-natured joshing about Vito’s shop.

The perfect town-hall answer, Klain thought.

That night, for the final mock, Kerry was instructed to bring his A-game. With the team on pins and needles, Obama earned a solid B-plus. The contrast with the previous night was so dramatic it called to Axelrod’s mind the triumphant scenes in Hoosiers. When it was over, the team rose in unison and gave Obama a standing ovation.

“All right, all right, all right,” the president said, waving them off, smiling abashedly.

The next morning, before setting off for Hofstra, the team gathered once again in Obama’s hold room to review the mock. No one was remotely certain they were out of the woods. The past three days had carried them too close to the abyss for firm convictions of any kind. But the president’s mood could not have been more buoyant. Running through the team’s critique, he reveled in their praise of a particularly strong answer.

“Oh, you guys liked that?” Obama said, grinning broadly. “That was fast and hammy, right?”

For all the progress Obama had made in his final practice session, his team was far from serene as the witching hour approached at Hofstra. Backstage, Klain was a nervous wreck. One pretty good mock, one disaster in the past 48 hours, Plouffe thought. So which Obama shows up?

Just then, the president emerged from his holding room a few minutes before heading onstage. He found Klain, Plouffe, Axelrod, and Jim Messina in the hallway.

“Guys, I’m going to be good tonight,” Obama said. “I finally figured this out.”

When the lights went up, it took all of one answer for the Obamans to realize that the president wasn’t kidding. Replying to the first questioner, a 20-year-old college student worried about finding work after graduation, Obama locked eyes with the young man and spoke crisply and pointedly. In the space of six sentences, the president plugged higher education and touted his job-creation record, his manufacturing agenda, and his rescue of the auto industry—plunging an ice pick into Romney by invoking “Let Detroit Go Bankrupt.” When Mitt cited his five-point economic plan in answer to a follow-up from Crowley, Obama let loose with his one-point-plan zinger. He was fast. He was hammy. He was gliding around the stage.

In the staff room, Obama’s increasingly giddy team kept track of his progress, using his debate-on-a-page as a scorecard, ticking off the hits one by one as he delivered them. On outsourcing to China, immigration (self-deportation), women’s issues (Planned Parenthood), and more, the president was not only proving himself an able student but making Romney pay for every rightward lunge he had taken during the nomination contest.

Romney responded aggressively but with visible annoyance as he found himself forced to keep doubling back to answer attacks from minutes earlier, which made him appear petty and threw him off rhythm. In Denver, Mitt’s propensity for gaffes had vanished as if by magic; at Hofstra, presto-change-o, it returned. Boasting of his commitment to gender equity in the Massachusetts statehouse, he referred to the résumés he reviewed for Cabinet posts as “binders full of women.”

About two thirds of the way through the 90 minutes, Romney tried to roll out a hit on Obama’s financial portfolio. “Mr. President, have you looked at your pension?” Romney asked.

“You know, I don’t look at my pension,” Obama said without missing a beat and with a mile-wide smile. “It’s not as big as yours, so it doesn’t take as long.”

The debate was now a little more than an hour old. The next question from the audience had to do with Benghazi. Obama explained the steps he had taken in the wake of the September 11 attack on the U.S. diplomatic mission there—and then turned his attention to his opponent. “While we were still dealing with our diplomats being threatened, Governor Romney put out a press release trying to make political points,” the president said sternly.

Romney got in a jab about the inappropriateness of Obama having taken a political trip on September 12. But Romney went further. “There were many days that passed before we knew whether this was a spontaneous demonstration or actually whether it was a terrorist attack,” he said. “And there was no demonstration involved. It was a terrorist attack, and it took a long time for that to be told to the American people.”

Obama summoned his highest dudgeon and responded: “The day after the attack, Governor, I stood in the Rose Garden, and I told the American people and the world that we are going to find out exactly what happened, that this was an act of terror. And I also said that we’re going to hunt down those who committed this crime. And then a few days later, I was there greeting the caskets coming into Andrews Air Force Base and grieving with the families. And the suggestion that anybody in my team, whether the secretary of State, our U.N. ambassador—anybody on my team—would play politics or mislead when we’ve lost four of our own, Governor, is offensive. That’s not what we do. That’s not what I do as president. That’s not what I do as commander-in-chief.”

Obama returned to his stool and took a sip of water. Romney, incredulous, began to splutter.

“You said in the Rose Garden the day after the attack it was an act of terror? It was not a spontaneous demonstration? Is that what you’re saying?”

With an icy stare, Obama set a trap: “Please proceed, Governor.”

“I want to make sure we get that for the record, because it took the president fourteen days before he called the attack in Benghazi an act of terror,” Romney insisted.

“Get the transcript,” Obama said—at which point Candy Crowley interceded.

“He did, in fact, sir,” Crowley said to Romney. “He did call it an act of terror.”

“Can you say that a little louder, Candy?” Obama said, twisting the knife in Romney’s back. The crowd burst into laughter and applause.

Minutes later, the debate was over. The Obamans were ebullient. The president’s performance hadn’t been perfect, but judged against the standards of Denver (or the Mock From Hell) it was pure genius. As he came off the stage, Obama thought he had done well. But having initially misjudged his performance the last time out, he was slightly tentative.

“That was good, right?” Obama asked.